9. August 2023

St Moritz Church, Augsburg, Germany (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum)

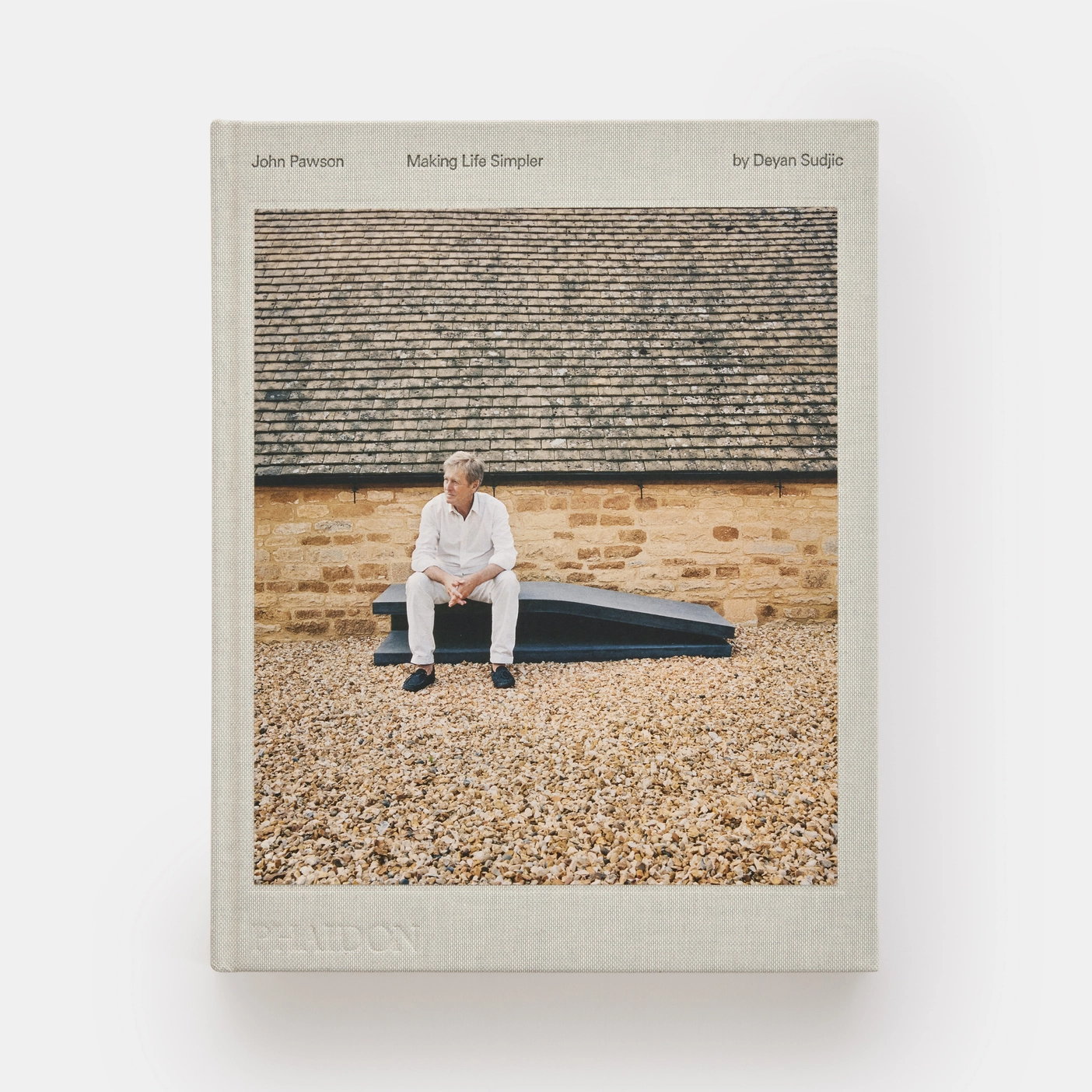

Recently, London-based architect John Pawson celebrated the release of his latest monograph, Making Life Simpler, authored by Deyan Sudjic and published by Phaidon. In Vladimir Belogolovsky’s interview with Pawson, he discusses key references and influences, his design process, what makes a building architecture, working with Calvin Klein, and his favorite place in London.

John Pawson started practicing architecture quite late. He did not study architecture until the age of 30, when he was accepted into the Architectural Association (AA) in London. He attended classes there from 1979 until 1981 without ever completing the course or receiving his degree. His education was based more on his extensive travels in Europe, Egypt, the Middle East, India, Australia, and the United States immediately after his schooling at Eton. Upon returning to England, he worked for several years at his family’s textile factory in Halifax, West Yorkshire, where he was born (in 1949) and grew up. He then spent a few years living in Japan, teaching English and socializing. In Tokyo, he met and became close with renowned architect Shiro Kuramata. Even though Pawson was never employed by Kuramata, their friendship allowed him to absorb many of the innovative architect’s techniques, details, and sensibilities. Apart from traveling internationally, Pawson explored many historical structures in Yorkstone, particularly industrial buildings built very solidly and — from the floors and walls, to the ceilings and roof tiles — seemingly entirely out of stone.

Pawson’s studies at the AA were interrupted in 1981 by his readiness to practice. He founded a design company with Italian architect Claudio Silvestrin and worked on projects with Crispin Osborne and John Andrews, two AA professors. All four combined their efforts to start a practice together, though it did not last. Currently, Pawson’s eponymous office, located near King’s Cross, numbers about 20 architects.

The architect’s most celebrated works include the new Abbey of Our Lady of Nový Dvůr in Bohemia, Czech Republic; the Calvin Klein flagship store in Manhattan; the Lake Crossing at the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London; and the Design Museum, also in London.

St Moritz Church, Augsburg, Germany (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum)

Vladimir Belogolovsky (VB): When you started building your projects in the 1980s, primarily minimalist interiors, they came as a strong contrast to what architects and designers were preoccupied with at the time, which was driven by postmodernist aesthetics: radical forms, shapes, bright colors, and lots of quotations from history. Where did your minimalist language come from? What were some of your references?John Pawson (JP): When I first went to the AA for an interview, I had to show them something. So, I presented my ideas for a bath and a washing basin. And they said to me, “Well, those are just boxes. Where is the design?” Of course, Zaha Hadid was queen at the time. The kind of work I did was unique then. I was following works similar to Donald Judd and a range of other minimalists who were not popular at the time. How did I come to that? Well, the only real design experience I had was in Japan with Shiro Kuramata. There I saw the first tea house, the Katsura Imperial Villa, and the temples. I also visited the Shaker communities in America. And memories of childhood visits to ruined Cistercian abbeys in Yorkshire, like Fountains Abbey and Rievaulx Abbey—entire cities in miniature, stunning, in terms of their qualities of proportion and simplicity and every bit as impressive in their way as anything I later saw in Egypt and Greece. But other people visited these places too. Why was I drawn to them so strongly?

JP: Yes. The most impressive for me was the Row House in Sumiyoshi, Osaka called Azuma House, completed in 1976: a narrow house with an open courtyard between the back and the front. I obviously also visited other things by him. It is hard to analyze what influenced me the most because it all happened naturally. But I would still say that my mother was a much more direct influence. I would also credit my father for the drive, which was latent in me, as I was quite relaxed initially. He liked beautiful things and he liked the best of things. He was also into architecture and even wanted to be an architect himself.

John Pawson Office, London, 2010 (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Making Life Simpler)

VB: You said, “Starting with a blank piece of paper isn’t as frightening as it used to be.” Could you take me through your design process? How do you typically start a project?JP: Ideally, we do start with the blank piece of paper. Although it takes more time than we normally have. It is difficult because clients think that you will have an immediate idea as soon as you visit the site. So, they constantly ask, “What do you think? What do you think?” But there is so much to take in — the site, the existing buildings, the weather, and so on. I do have the ability to take in everything. Then we sit down with my team and I do my naïve sketches and say what I think we want. Then they very kindly go away and do it properly. And when they come back, I say, “Well, that’s not what I want!” Then we have an argument. And I go away thinking that I won the argument. And I come back, but they haven’t done it. So, we have these back-and-forth interactions. They are all very good designers and independent people. But I am the one who has to make a call. And, sometimes, I lose. [Laughs] I have five people who have been with me for over 20 years. Others who have been with me for 10 years. And, of course, we have new people in their 20s, who just arrived.

JP: They have. For sure. We are the sum of the parts, definitely. The one thing I try to get them to avoid is doing what they think I would do. I don’t want pastiche. Of course, there is an office ethos. So, they would pick up and do things that are within the range of what we do. But, hopefully, in new ways. So, I try to surprise them.

JP: Not directly. I use them as a resource. I had an idea, so I took a picture. And I want to keep it because I want to remember it and share it with my team. These photographs are very abstract. Years ago, Phaidon picked up on that and made a book called Minimum. Before that, I never thought of myself as a photographer. But now I am a photographer. [Laughs]

Home Farm, Oxfordshire, England, 2019 (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Making Life Simpler)

JP: If you are not affected when you walk into a building, then I don’t think it is architecture. At least that’s a good measure of what architecture is. Architecture must have an atmosphere. It does not need to be grand like a cathedral. It could be something very modest, but it has to have a physical effect on you.

JP: Yes. I never really counted. It is just a guess. But when I had just started, I would often say to my potential clients, “Just give me a house or a new building and I’ll show you what I can do.” Because in the early years, I would mainly do interiors such as art galleries. I took them very seriously and it is really important to design spaces that suit art. But, of course, what suits the art makes the space that contains it somewhat secondary. I remember showing people my art gallery interiors and they would say, “But what have you done?” [Laughs] People could not notice my work. Of course, in those days, in the early 80s, people had done white boxes. But they were not common then.

Calvin Klein New York, 1995 (Photo: Todd Eberle, from John Pawson: Making Life Simpler)

VB: By the time Calvin Klein asked you to design his flagship store on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, did you have your design ethos defined, or did it take your work to a new level?JP: The new level was simply in the fact that it was connected to Calvin Klein. Suddenly my work was exposed to a huge public, far beyond what I had in England and far beyond the scale of any of my projects before that moment. Not only did he change my career, but he also changed my life. But my ethos, philosophy, and aesthetics were already there. So, the store was a continuation of what I was already doing. Another difference was in the fact that it was for Calvin and he would like to be an architect. He liked drawing and designing interiors. He had strong ideas that he liked to put into practice. Anyway, we worked together, or rather I was helping him to get the store that he wanted. It was his vision but there were lots of decisions that were mine. He likes lots of contrasts, such as black and white. As we worked on the final stages of the design, he kept asking for less clothing and fewer things. Only he could dare to do that. His retail director, Gabriella Forte, who was running the company and who was an expert on fashion and selling clothing, wanted to pile it high. And he kept taking everything out. It was very funny. When it had just opened, I remember sitting there and watching people’s faces. They were coming and they were not there to buy clothing. They came to look around. But he was very cool about that. It didn’t have to sell from day one. It was a reflection of his ethos.

JP: Often the first I hear about a visit is when members of another community or church get in touch with the office, asking if I will do work for them. The commissions at the Catholic church of St. Moritz in Augsburg in Germany and the Benedictine Archabbey of Pannonhalma in Hungary each came directly as a consequence of the experience of being at Nový Dvůr. Since then, I have also worked on religious buildings in Britain and Italy. When Calvin was designing his house, he wanted to see the monastery in the Czech Republic and we flew there together in his private jet. It has become a reference for many clients.

Perspectives installation, St Paul’s Cathedral, London, 2011 (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum)

VB: What is your favorite building or place in London?JP: In 2011, I was asked to do work in St. Paul’s Cathedral and, as a consequence, I gained access to every bit of the place. It was amazing. I worked on a temporary installation called Perspectives at the foot of an exquisite 17th-century spiral staircase. And because I had to work in other parts of the building, the head custodian, who was quite busy, ended up handing me the whole keyring of St. Paul’s Cathedral with some of the original keys on it. So, for about a day I had access everywhere and I went to as many places as I could manage, including the Whispering Gallery that circles the base of the dome structure, accessed through a private staircase. From the Whispering Gallery, you have a vertiginous view of pretty much the entire cathedral floor plan. It was such a thrill.

John Pawson (Photo: Gilbert McCarragher, from John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum)

John Pawson: Making Life Simpler

Deyan Sudjic

304 × 238 mm (12 × 9 3/8 in)

296 Pages

230 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9781838666194

Phaidon

Purchase this book

Related articles

-

'Architecture Must Have an Atmosphere'

on 8/9/23

-

The Poetic and the Pragmatic

on 4/21/22

-

Novelty Is Nonsense

on 4/7/17