2014 Venice Biennale: Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014

John Hill

18. June 2014

Austria Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: Markus Bachmann

The Fundamentals theme for the 14th International Architecture Exhibition consists of three components: Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014, Elements of Architecture, and Monditalia. Here we look at the national pavilions and Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014.

See also our coverage of the Elements of Architecture and Monditalia, and some of the collateral events.

Unlike previous years, when the participating countries were free to fill their pavilions in the Giardini, the Arsenale or elsewhere in Venice with whatever content and theme was to their choosing, Biennale Director Rem Koolhaas gave each of the 65 countries one theme to address: Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014. He asked that the countries "examine key moments from a century of modernization," in order to "reveal how diverse material cultures and political environments transformed a generic modernity into a specific one."

Here we highlight 20 of the 65 national pavilions, starting with our 10 favorites and followed by 10 notable pavilions; each grouping is shown in alphabetical order.

Ten of the Best

Austria Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: Markus Bachmann

Austria

Plenum. Places of Power

Nearly 200 1:500-scale models sprout from the walls of the Austrian Pavilion, each one depicting a parliament building in a basic white that matches the paint on the walls. Commissioned by Christian Kühn, the models allow for direct comparisons in terms of size, layout, symmetry, ornament and other architectural traits. A creative guide – closer to a swatch of paint colors than a traditional book – adds maps, site plans, and numerous demographic, economic and environmental data to the comparative mix.

Austria Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: Markus Bachmann

Belgium Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Belgium

Interiors. Notes and Figures

Easily the most austere pavilion is the one curated by Sébastien Martinez Barat, Bernard Dubois, Sarah Levy, and Judith Wielander, where the rooms of the Belgian Pavilion are made up of a series of architectural interpretations based on how people transform their homes. The pavilion is incomplete without the pages of the study, which show full-color photographs of what appear to be unremarkable residential spaces, but ones that are made personal by, for example, reconfiguring a kitchen to also work as a living room or making a bathroom double as a closet.

Belgium Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Canada Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Canada

Arctic Adaptations: Nunavut at 15

According to the curators at Lateral Office, "the climate, geography, and people of the Canadian Arctic resist modernism's universalizing agenda." Nevertheless, "southern models of buildings" have been exported to the Canadian Arctic in the last 100 years, and the exhibition consists of carved depictions of significant buildings in this timeframe, made by residents of Nunavut ("our land"), Canada's most northern territory that is celebrating its 15th anniversary, after separating from the Northern Territories on April 1, 1999. The unique circumstances and excellent presentation helped the Canadian Pavilion to earn a Special Mention for National Participation.

Canada Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Chile Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Chile

Monolith Controversies

It would be easy to walk by Chile's pavilion and dismiss it outright, since only a pink-walled living room whose coziness hardly speaks about modernity is visible. But a few steps in and to the right and the visitor is confronted with a dark space inhabited by a precast concrete panel, the same sort of panel that made the container for the living room. Curators Pedro Alonso and Hugo Palmarola focus on this 20th-century object – built by the Chilean KPD plant in 1972 with help from the Soviet Union during the "Chilean road to Socialism" – not only for the fact KPD built 153 housing blocks from the precast system in Chile, but for the reported 170 million apartments built during the second half of last century worldwide. The sharp focus and dramatic presentation earned Chile a Silver Lion for National Participation.

Chile Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

France Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

France

Modernity: promise or menace?

Biennale Director Rem Koolhaas set the starting date of modernity as 1914, the start of World War I. Jean Louis Cohen, curator of the French Pavilion, marks this year in France as a change from Beaux-Arts architectural composition to a shaping of modernity "in response to the expectations of different parts of society." Cohen fills the center of the 1911 pavilion in the Giardini with a large model of Villa Arpel, the architectural star of Jacques Tati's 1958 film Mon Oncle. Radiating from this utopian absurdity are rooms with the country's "brilliant successes and failures," such as one devoted to Jean Prouvé's prefab architecture (below), with clips from various French films uniting everything. The French Pavilion earned a Special Mention for National Participation.

France Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Great Britain Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Great Britain

A Clockwork Jerusalem

Before the doors to the Giardini opened on June 7, it was known that FAT's (Fashion Architecture Taste) swan song would be the pavilion of Great Britain, which they curated with Crimson Architectural Historians. That their finale would consist of a conical pile of dirt could not have been foreseen. The pink landform and trippy mural around it ready the visitor for a journey through Britain that is equal parts history, science fiction and social reform. Imagination links the various threads filtered through Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange – Utopia of Ruins, Paleo Motorik, Welfare State Baroque, ... – with the hope, on the part of the curators, that imagination will "build our New Jerusalems."

Great Britain Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Japan Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Japan

In the real world

Amongst the apparent clutter – 55-gallon drums, wood palettes, shipping crates, scaffolding, construction fencing – a model of Toyo Ito's Dom-Ino System stood out on my first visit, perhaps because a few minutes earlier I had seen a full-scale version, in wood, of Le Corbusier's famous drawing. Ito's design, from 1982, is one of many projects that responds to various Japanese and international crises that arose in the 1970s, so it's less a copy of Corbu's diagram than a reconsideration of it for a new reality. Similar sentiments can be applied to other projects in the pavilion that curator Norihito Nakatani describes as "desperate efforts to redefine architecture by learning from life in the real world."

Japan Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Korea Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Korea

Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula

Commissioner Minsuk Cho of Mass Studies calls "Crow's Eye View" (the name is inspired by a 1934 poem by Korean architect-turned-poet Yi Sang) "a prologue for a yet unrealized joint exhibition of the two Koreas, what we would call the 'First Architecture Exhibition of the Korean Peninsula'." By presenting the architecture of North and South Korea, from an admittedly South Korean point of view, Cho and fellow curators Hyungmin Pai and Changmo Ahn try to erase the oversimplifications and clichés that people carry with them in regards to the peninsula. The thorough and densely packed pavilion earned the Golden Lion for National Participation.

Korea Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Russia Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Russia

Fair Enough: Russia’s Past our Present

In 2012 Russia wowed visitors with an immersive experience of QR codes lining the walls of their pavilion. A much different type of experience takes place in this Biennale, where actors sit at tradeshow-like kiosks and interact with visitors donning tradeshow badges. The commercialization of architecture is obviously the point of the Strelka Institute's curating, but the pavilion's uncanny resemblance to a trade fair makes for an experience equal parts enlightening, humorous and unsettling. Russia's theatrics earned the pavilion a Special Mention for National Participation.

Russia Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

USA Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

United States of America

OFFICEUS

Rather than presenting architecture on American soil, the United States Pavilion, curated by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Ana Miljački, and Ashley Schafer, looks abroad to the production of American firms building overseas. Their presentation consists of two parts: a collection of research on 1,000 projects by 200 architects that lines the walls of horseshoe-shaped pavilion; and "an active, global, experimental architecture office that researches, studies, and remakes projects" from said research. The courtyard is used for discussions and other events for the six-month duration of the Biennale. Combined with the working office inside, the pavilion, like Russia's, promises to be a lively one in more than one sense of the term.

USA Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Ten of the Rest

Argentina Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Argentina

IDEAL / REAL

The intersection of modern ideas (IDEAL) and the design of Argentinian cities (REAL) through a succession of periods in the 20th century is the approach of curators Emilio Rivoira and Juan Fontana. Argentinian cinema bridges these two realms, as it's seen as "a fiction that shows the REAL world."

Bahrain Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Bahrain

Fundamentalists and Other Arab Modernisms

Bahrain may be a small island nation with a population of only 1.2 million, but curators George Arbid and Bernard Khoury took it upon themselves to document a selection of architecture from the Arab World (a population of more than 400 million) in the last 100 years. Their research is documented in a book that lines the circular shelves of their pavilion in the Arsenale. As visitors go home with the books the circular space will become more and more open.

Brazil Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: Markus Bachmann

Brazil

BRAZIL: MODERNITY AS TRADITION

According to curator André Corrêa Do Lago, "in spite of Brazil's centuries of rich architectural heritage, what is known as 'Brazilian Architecture' is not the architecture of the past, but its modern architecture." As more and more people eye the country that is hosting the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, the depth of its great modern architecture is being exposed to an even larger international audience.

Denmark Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Denmark

Empowerment of Aesthetics

One of the two main rooms of the Danish Pavilion is devoted to artifacts under glass, but it's the larger room with bark, roots, earth, light and other "fundamentals" that is appealing for its sheer sensorial impact. Very few pavilions hit the visitor with distinct smells and textures, but the Danish one excels at such an experience.

Germany Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Germany

Bungalow Germania

The German Pavilion in the Giardini was built in 1939, but its architecture is more in tune with Albert Speer's stripped classicism than Mies van der Rohe's fluid modernity as expressed in the Barcelona Pavilion ten years earlier. Alex Lehnerer and Savvas Ciriacidis have recreated Sep Ruf's thoroughly modern Chancellor Bungalow from 1964 (used officially until 1999, when the German capitol was moved from Bonn to Berlin), such that the pavilion "swallows it" while also creating a conversation between the two architectures.

Israel Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Israel

The Urburb

Curators Ori Scialom, Roy Brand and Keren Yeala Golan explore patterns of contemporary living by turning Israel's pavilion into "a contemporary construction site furnished with four large sand-printers." Last century's tabula rasa planning is the main culprit in the exhibition's neologism of an urban/suburban mesh, enabled by top-down planning and illustrated by a sweeping away of the sand after each "urburb" is "printed."

Italy Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Italy

Innesti/Grafting

Italy disembarked from the Central Pavilion to the Arsenale to make way for Rem Koolhaas's Elements of Architecture exhibition. Cino Zucchi has curated a four-part exhibition (Milan: Laboratory of Modernity, Cut and Paste Environments, A Contemporary Landscape, and Inhabited Landscapes) that is united by the theme of "Grafting," where in his words "contemporary thought pursues new goals and values through a metamorphosis of existing structures."

New Zealand Pavilion, Palazzo Pisani Santa Marina. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

New Zealand Pavilion

Last. Loneliest. Loveliest

Of the 65 national pavilions participating in the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, 10 of them are first-time participants. New Zealand is one of those ten first-timers, but it is also one of ten pavilions located in Venice beyond the Arsenale and the grounds of the Giardini. A gallery in the ground floor of a palazzo near the Rialto Bridge references, as curator David Mitchell describes it, "the Pacific way of building ... a lightweight architecture that's comparatively transient" and evident in recent buildings like the Auckland Art Gallery and Shigeru Ban's Cardboard Cathedral.

Switzerland Pavilion, Giardini. Photo: Markus Bachmann

Switzerland

Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price. A stroll through a fun palace

Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist's high-profile pavilion assembles some big names in the worlds of architecture and art – Herzog & de Meuron, Atelier Bow-Wow, Elizabeth Diller, Olafur Eliasson, Dan Graham, ... – though visitors will be hard-pressed to recognize their contributions. More performance than presentation, the pavilion brings together a Swiss sociologist and an English architect through minimal design and the occasional activation of the space through archives (photo above), light shows and schools inhabiting the pavilion for the duration of the Biennale.

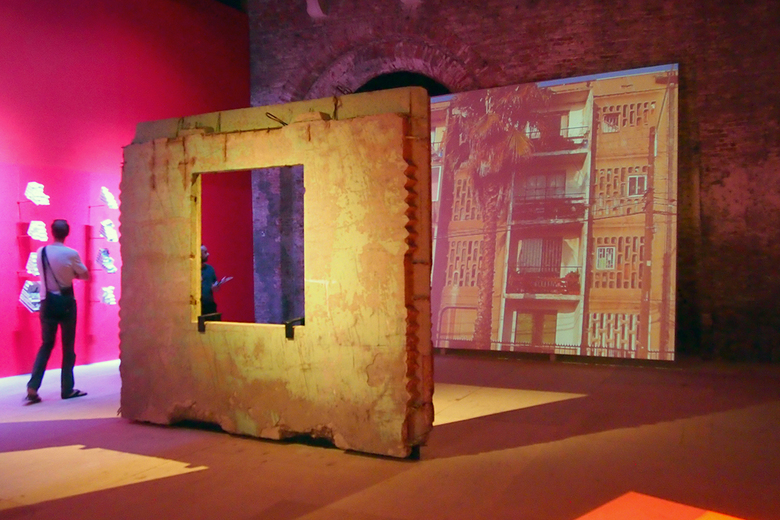

Turkey Pavilion, Arsenale. Photo: John Hill/World-Architects

Turkey

Places of Memory

Along with New Zealand, Turkey is one of the first-time participants included here, though its location in the Arsenale is relatively larger, enabling curator Murat Tabanlıoğlu to invite five architects/artists to present work focused on three areas of Istanbul. Perceptions and experiences are the means of exploring the Absorbing Modernity theme, starting with the curator's own memories. Likewise the collaborating architects look at, per Tabanlıoğlu, "the concept of place itself, incorporated with the subjective vision of every exhibitor on the team."

See also our coverage of the Elements of Architecture and Monditalia, and some of the collateral events.

Related articles

-

Abbot Kinney

on 6/19/23

-

The Rose Apartments

on 10/25/22

-

Art at The Cutaway

on 3/22/22

-

'We must arrive at a happy contentment'

on 3/10/22